In Jacksonville, Florida, in 2012, Marissa Alexander was sentenced to twenty years in prison for firing a single warning shot in the air to protect herself and her nine-day old infant from her abusive husband. Florida’s infamous “Stand Your Ground” law which allowed George Zimmerman, a neighborhood vigilante, to murder Trayvon Martin, a Black teenager, with impunity, did not protect Marissa. In 2014, Marissa accepted a plea deal and has been serving a two-year probation sentence within her home.

Marissa’s case is far from unique. Tondalo Hall, a 30-year old mother from Oklahoma, is serving a 30-year sentence for “failing to protect” her children from the man abusing her and her children. Her sentence is 15 times that of her abuser. Failure to protect implies Tondalo, a survivor of domestic violence, is somehow responsible for her abuser’s actions. The criminalization of victims, especially of women of color, is a key tenant of the U.S. prison industrial complex. There are more women in prison in the United States than any other nation, and nearly 90% of incarcerated women are victims of domestic and sexual violence and child abuse.

Victims of sexual and domestic violence are shamed for not fighting back and criminalized for self-defense. This is rape culture. Rape culture refers to the intersecting forms of oppression which sustain the inevitability of sexual and domestic violence by blaming victims.

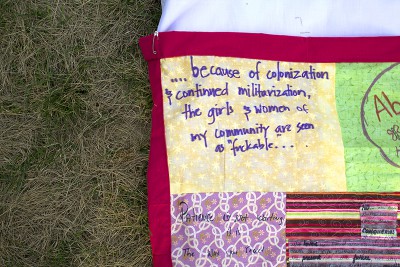

In such a culture, it can be nearly impossible to create spaces to process and heal. The Monument Quilt is a public healing space by and for survivors of rape abuse. The bright red, hand-sewn quilt series holds space for more than 500 narratives and messages.

Teonia Burton, an activist and healer, facilitated a healing space at a display of the Monument Quilt in Jacksonville, Florida, on the court steps outside Marissa Alexander’s hearing in January of this year. Teonia described the importance of Free Marissa Now campaign. “It’s an important campaign because those types of incidents happen more often in the United States than people are aware of. I think people are unaware of how common it is for a survivor of domestic violence to be placed in prison when they were simply trying to defend themselves. In Marissa’s case, no one was even hurt. Her crime was defending herself and her baby, and she was being sentenced while her abuser went free.”

Teonia identifies herself as a healer and advocate. Teonia explains, “I use that title for myself because I believe we all have an ability to facilitate healing in ourselves and each other.” Teonia’s background as a doula and midwife gave her insight into supporting people in moments of immense vulnerability. “My healing work is involved in supporting families during the prenatal period, labor, birth and postpartum. Most of that involves supporting people during the emotional aspects of pregnancy and being responsible for caring for a pregnant person who may not know much about nutrition. That’s where the healing aspect of my work comes from. I’m open to listening, and quite often people open up to me and share deeply personal stories that I am able to listen to without judgment, keep sacred, and hold space for.”

Participating in the Monument Quilt display in Jacksonville had a major impact on Teonia. “To be able to lay out the quilt and meet the coordinators was very inspiring because I have never been involved in a public healing space for survivors of domestic violence and abuse. Just this past year, I started seeing myself as a survivor, understanding that I have a story. In order to go through a healing process, I must share the story and live through it. So actually seeing the quilt, displaying it, and being involved in holding space for those impacted by violence during the workshops and the display, it was just a sacred moment and a sacred space for me.

“It was a privilege to be there to listen to everybody’s story. Each story is intensely personal and takes a lot of courage for people to share. I was so used to just listening to others, but watching others have the courage to share their stories gave me the encouragement to start sharing my story and to start working through my own healing process. I was just really grateful to be personally involved with this quilt because it inspired me to find another way to participate in social justice and to participate in healing in a different way. I never imagined a healing space displayed as a quilt and displayed in a public way.”

Teonia recently joined the Monument Quilt team as the National Outreach Consultant. “Creating and maintaining public healing spaces for survivors of sexual abuse and domestic violence is one of the strongest and courageous acts of healing justice for our communities. Representing FORCE as their National Outreach Consultant gives me the privilege to participate in social justice in a way that complements my purpose as a healer and work as a midwife.”

Teonia explained that a public healing space serves many purposes: to create space for survivors to process, to educate and raise the consciousness of communities, and, potentially, to provide an opportunity for restorative justice.

Restorative justice prioritizes reparations for harm, centers victims, and involves perpetrators, victims, and community members in creating sustainable, transformative alternatives to the prison industrial-complex.

“Using public healing space for survivors of sexual abuse and domestic violence is a process I think could be used for what we refer to as restorative justice, especially in small communities. I grew up in a rural community, and if a person is assaulted or abused, most of the time, that person is related to their abuser or they know that person. That makes it especially hard for people to share what the incident was or seek support. Public healing spaces will bring to light in those small towns ways to make this issue public. Not only the survivor but also the perpetrator has the opportunity to possibly seek healing as well. I haven’t really sat down and thought about how that process could work, but I think healing spaces give all of us an opportunity for conversations, awareness, and restoring social order in communities. I know that public displays of healing can also work in larger communities, but I really think about where I grew up and where I’m living – it could be another resource to use.”

Many falsely assume that restorative justice means a lack of accountability for perpetrators. Without incarceration, how do we hold abusers accountable for their violence? While this is a complex question, it is important to consider the ways in which restorative justice actually expands rather than limits accountability for violence within our society and communities. By centering the victim’s need for healing and support, restorative justice actively engages entire communities. Restorative justice requires communities be critically aware of the ways in which they perpetuate rape culture and challenges all members to hold themselves accountable to fostering a culture of consent, in which sexual violence is never condoned and survivors are unconditionally supported.

To learn more about how you can support Tonaldo Hall and fight the criminalization of self-defense, read about our call to action. To create your own quilt square for the Monument Quilt or to bring the Monument Quilt to your community, visit themonumentquilt.org.